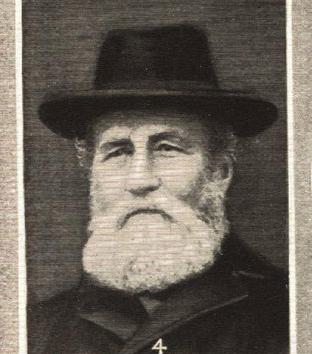

1835 — 1914

James Meadows

Served for fifty-two years with China Inland Mission, a long-time supporter and friend of Hudson Taylor.

James Joseph Meadows was converted to Christianity at Perth, Scotland. He later lived at Barnsley, Yorkshire.

In 1860, J. Hudson Taylor, who had worked as a missionary in Ningbo (Ningpo), was back in England to recover his health, calling for recruits to help with that work. Meadows was already serving as a witness for Christ when his Methodist Class Leader suggested that he go to China as a missionary. “I said, ‘I will go,’ but asked for time to pray about it. So I fasted and went into my little workshop and knelt down one dinner time … and asked the Lord ‘Shall I go?’ The answer that I got there and then was, ‘Go, and the Lord be with you’” (Broomhall 3.245).

In October 1861, he moved to London to learn Chinese from the Taylors and their Chinese helper Wang Lae-djun. At twenty-six, he was three years younger than Hudson Taylor. He was immediately struck by Taylor’s “strong yet quiet faith in the promises of Scripture, his implicit confidence in God, this it was which compelled submission on my part to whatever he proposed for me” (Broomhall 3.270). On his part, Taylor wrote that Meadows gave him and Maria “unmixed satisfaction” and began to plan for his departure for China.

He went home at Christmas to marry his fiancée Martha. Suddenly, a fast ship became available, so the new couple sailed on January 7, 1862 for Ningbo, the first two of five reinforcements whom Taylor sought for the “Ningbo Mission,” as it was now called. They landed in June, just after the city had been liberated from the Taiping rebels. He was learning the language but not fast enough. He chafed with frustration at not being able to preach in Chinese yet! His wife fell dangerously ill. Martha progressed much more slowly, not being a student and depending on learning a few words and phrases from their Chinese serving woman.

The Taiping rebels had been driven from Ningbo, but they returned and threatened the city again. Meadows confessed to being anxious, “but as soon as I look to the Lord, He gives me grace to surmount the fears and doubts; and sometimes I have felt as though I would die like a martyr shouting out ‘glory to God’” (Broomhall 3.300).

Meanwhile, he worked hard at learning Chinese. Within a year, he could deliver a simple Christian message in the language. He also ran a school for Chinese boys, taught by his Chinese instructor, traversed the city with tracts and Scriptures, and visited Christian homes with a Chinese evangelist. He was learning how to live among them, sharing their danger and privations. He was also learning lessons of faith. When Taylor’s agent in Ningbo inadvertently told Meadows that Taylor had given him money to disburse to Meadows regularly, he responded that he wanted to live only by faith in God, relying upon him alone and not upon any man.

Though not formally educated or ordained, Meadows was becoming indispensable to the little Bridge Street church. “He was wholly absorbed in his work, visiting wealthy Chinese in their homes and official quarters, and always courteously received… But although Meadows’s Chinese was improving, only a faithful three or four would come to his Bible classes in July, and by August none at all. In the great heat all were prostrated” (Broomhall 3.316).

The weather turned cooler in September, but Martha died suddenly of “Ningbo cholera.” James wrote to Taylor: “The Lord has turned my Eden into a wilderness place. And has made me desolate… She is gone, the living one is gone… She has entered into peace, she is at rest in her bed, and because, Lord, thou hast done it, I will be silent, Thou shalt find no murmurings in my heart at Thy ways… I want Thee to tell me why, so that I may know how to improve [that is, make spiritual use of] her death as Thou, my loving God wouldst have me” (Broomhall 3.316).

Another missionary wife who had lost a child took his child and cared for him, and Chinese friends showed kindness and sympathy. Burial expenses left him penniless, but he wrote “God is faithful” and trusted him to provide. “If I were to say that I have not lacked I should tell lies, but I have lacked such things by God’s good providence … that would be esteemed by some folks indispensably necessary to their comfort and almost their existence” (Broomhall 3.320). He had learned to live simply among the Chinese.

Still grieving several months after Martha’s death, he wrote, “I know why God afflicted me, ‘That I might be a partaker of his holiness,’” and went on to quote Scripture promises of God’s unfailing presence (Broomhall 3:321).

With the death of Dr. William Parker and the departure of John and Mary Jones, the Bridge Street church was in the care of E.C. Lord and Meadows, in whom Taylor had increasing confidence. From a humble background, Meadows felt uncomfortable with most missionaries, who were all well-educated and cultured, so he spent his time with Chinese Christians, and thus “progressed in language and understanding of them far faster than he would have done with his own home and colleagues to keep him isolated” (Broomhall 3.371). One Chinese Christian wrote of him, “He is both diligent in the work of God, and speaks the Ningpo dialect very well. He and I are most intimate friends” (Broomhall 3.376).

Aside from pastoral work, he went often with the most active Christians to preach both in the city of Ningbo and in the countryside, where he encountered both the physical and spiritual needs of the teeming populace. He also joined with another missionary to rent part of a temple in a market town thronged with people from the countryside three days a week, whom they found very receptive to the gospel.

In Ningbo, more and more attended worship services and his Bible class. First one and then another requested baptism. The church was outgrowing his ability to pastor them effectively.

Though living in the Bridge Street premises with George and Annie Crombie, new members of the Ningbo Mission, he was lonely. He began courting by correspondence a close friend of Martha’s, Elizabeth Rose, from his home town of Barnsley. In 1866 he wrote to her proposing marriage. She accepted, and sailed with Hudson Taylor and the first party of new CIM missionaries on the Lammermuir in May, 1866.

Both before and after Taylor formally founded the China Inland Mission, Meadows fully understood and subscribed to the position of not trusting in gifts from Christians, but only in God himself.

Hudson Taylor took Elizabeth Rose to see her fiancé James soon after the Lammermuir landed in Shanghai. By this time James had a “good grasp” of the Ningbo dialect after four years’ residence there among the Chinese. A few months later, on November 30, he and George Crombie visited the new group of CIM missionaries in Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang Province. The next day, they went out preaching with Taylor. Interestingly, because he lived in a treaty port, Meadows had not changed into Chinese clothes, nor was he required to by Taylor. He did live more simply than other foreign missionaries, however.

When several men from the Lammermuir party rebelled against Taylor’s policy of wearing Chinese dress, Meadows and four others stood firm, though he would later vacillate at times.

At one point, Meadows and Crombie intervened with the local magistrate when a Christian was arrested. On the instructions of the consul in a letter to Taylor, he never repeated that mistake.

Though his main focus was upon the Chinese, in his encounters with other missionaries and consular officials, Meadows made a profound impression. Charles Schmidt, a former officer in the Army, was actually “converted at Ningbo through the zeal of James Meadow,” and later resigned his commission and became a missionary (Broomhall 4.322).

He was ever Taylor’s trusted associate. In the summer of 1867, he agreed to take Josiah Jackson, one of new missionaries, to Taizhou to “get him and [Feng Ning-gui] a Ningbo Christian established there” (Broomhall 3.323). When they arrived, Meadows found that his English dress drew unwanted attention: “Men and women, boys and girls, called after him, ‘red-haired man,’ ‘white devil,’ etc.’” (4.341). They found an upstairs room in a temple for temporary quarters, but they were robbed at night by thieves who let themselves down through the roof by removing the tiles. Meadows returned to Ningbo as soon as the other two had settled in.

His first child by Elizabeth died at birth in 1868. Not long afterwards, he travelled with the Crombies and Taylor to visit a church in Fenghua founded by CIM missionaries. In February, 1868, it was agreed that McCarthy would oversee the Ningbo church to free Meadows for pioneering work on the Yangzi, starting in Suzhou, where in April 1868 he rented and helped prepare premises for newer CIM missionaries to occupy, as part of Taylor’s strategy to strike out into new places.

He fully agreed with the CIM’s broad non-denominationalism that subsumed differences over secondary matters to the great cause of evangelization of China’s unreached millions. For example, though Methodist, he baptized the converts of Crombie, who was Presbyterian.

Taylor frequently sent him, alone or with another, to help CIM workers in other places. He and McCarthy went to Taizhou to help Jackson, for instance. Later, he and Williamson joined Taylor in spearheading exploration of unevangelized provinces. His family moved to Zhenjiang and then Nanjing so that he could return more easily to them. He left Nanjing December 26, “eventually to gain an uncertain footing in [Anqing] after months of hard work against determined opposition” by the sub-prefect, though they had been courteously received by the prefect and district magistrate (Broomhall 5.161-162; 202). At first, however, he resided in Anqing with Williamson, first living on a boat and then at an inn.

Though they claimed the right to rent premises in China under treaty provisions, they faced constant obstacles from officials, and the local people dared not be friendly to them. Finally, in April 1869, while Meadows was in Nanjing visiting his wife for the birth of their second child, Williamson was able to rent a house in a good and salubrious location. Elizabeth and her two children, who had lived at Nanjing, fifty miles away, with other CIM missionaries (George and Catherine Duncan and Mary Bowers), joined them on July 9.

As loyal to Taylor as he always was, Meadows sometimes wrote thoughtlessly, complaining of not receiving speedy replies to his letters from the overworked leader and even once asking for some soap.

Greater troubles were to come, however. As the regional literary examinations approached, when thousands of aspiring candidates would be in town, the magistrate wrote and asked that they leave town until the tests were over. An inflammatory placard was posted at the examination site, calling for students to destroy the mission home, so Meadows and Williamson ran to the magistrate’s office and called for protection. When they were finally received, a mob gathered outside to demand their deaths.

Meanwhile, another mob besieged their home. Battering down the doors, they swarmed inside and assaulted Elizabeth. They plundered the place, seizing everything they could. Then they turned on Elizabeth, taking what little money she had “secreted” on her person, along with her wedding ring, and even tried to take her baby from her. She was finally saved when the magistrate belatedly arrived. “A faithful Christian servant then took her hand and led her through the mob to join her husband in the yamen [magistrate’s compound). After dark they were given some bedding and money for food and, otherwise completely destitute, were put on board two little river boats, to go wherever they could” (Broomhall 5.216).

They made their way to Jiujiang, where friendly foreigners took them in, and then to Zhenjiang, where other CIM missionaries welcomed them. Elizabeth described their plight and her feelings with the words of Naomi in the book of Ruth: “Call me not Naomi, call me Marah … I went out full and the Lord hath brought me again empty.” Broomhall concludes: “Not one relic of their most prized possessions, personal mementoes of home and parents, remained to them” (Broomhall 5.217).

After both the French and the British made a demonstration of force, the provincial authorities ordered that the missionaries should be compensated for their losses and allowed to return to their ransacked home. At the Taylors’ suggestion, they contributed the money they received from the Chinese to a local fund, while the Taylors personally made up for their losses. Meadows moved back on February 23, 1870. He gave Elizabeth the option of staying away, but she bravely returned also, though “neither of them could shake off the pall of terror their home continually represented to them” (Broomhall 5.22).

So thoroughly was James Meadows shaken by the trauma they had been through that when a massacre of French people took place in Tianjin, he “returned to foreign dress for self-protection. To Hudson Taylor’s mind it was a sad departure from trust in God” (Broomhall 5.276). Eventually, in the fall of 1870, he and his wife moved to Shanghai for a while, to Taylor’s great sorrow. He requested that they be re-assigned to Ningbo, but Taylor withheld permission, because the church there had become fully indigenous – self-supporting, self-governing, and self-propagating. It would not help to have them become, once again, dependent upon a foreign missionary.

“After all they had been through, James and Elizabeth Meadows were preparing to return to Britain on leave. They left Zhenjiang for Shanghai on April 7 but were delayed by the premature death of Elizabeth’s baby and continuing ill-health, so that they decided to wait and travel with Hudson Taylor. They were still waiting in July. By the time they arrived home James would have been away for nine years of rebellion, war, riot, threats and recurring dysentery” (Broomhall 5.290). Aware of Taylor’s concern for his little son Charles Edward (Maria had died the previous year), Elizabeth offered to take him home with them. They finally left with Taylor and Jennie Faulding on August 5th. (Hudson Taylor and Jennie became engaged on that voyage.)

Meadows was in a very low state of health when he left China, but he recovered in England’s cooler climate. Soon, he was going with Grattan Guinness on a tour of a number of cities, talking about China and challenging young men to commit themselves to serve Christ there. He arrived in Shanghai with A. W. Douthwaite, a new worker, in May 1874. When John Stevenson, who was overseeing a church in Shaoxing, was designated elsewhere, Meadows was asked to take his place for a while. In the end, he stayed in that position for the next forty years, except for one furlough, until he died.

In October, 1874, he and Douthwaite were the victims of mob protesting the opening of a mission by two Chinese evangelists in Huzhou, not far from Hangzhou. Despite assurances from the local magistrate, they were robbed of almost all they possessed.

As we have seen, James Meadows was not always constant in his adherence to the basic principles of the CIM. Once, when Taylor visited them in Shaoxing in December, he found that Meadows had “again reverted to foreign dress, choosing to be like other missions rather than like the Chinese to whom he was effectively devoting his life.” We are not told the outcome of Taylor’s visit and exhortation, but Meadows’s “little daughter sat with her arm around Hudson Taylor’s neck while he encouraged her parents. (In time she joined the Mission)” (Broomhall 6.155).

When pondering which men to choose as superintendents of the Mission, Taylor saw Meadows as “a successful pastor but uneducated and half-hearted in his loyalty to Hudson Taylor.” Still, he remained a trusted friend and associate for Taylor, who often wrote to tell him of his latest plans for expansion of the CIM. In 1886, Taylor overcame his reservations about Meadows and named him Superintendent for Zhejiang, though he was “himself rebellious against wearing Chinese dress, with gentle James Williamson to mollify him. Responsibility as superintendent could bring Meadows to personal compliance with the Principles and Practice,” the newly published manual for workers in the CIM (Broomhall 6.386).

In later years, Meadows wrote nothing but high praise for Taylor. He spoke, for example, of Taylor’s “affectionate reverence [for God] which made the godliness of the good man stand out conspicuously” (Broomhall 7.441). He remembered how, when they were sailing home to England on furlough, Taylor had responded to Meadows’s complaining about his accommodations by inviting him to share the second class cabin that the captain had given him.

Elizabeth Meadows died in November 1890 “when nine foreigners and eight Chinese were ill with influenza in the same house” (Broomhall 7.140).

James Meadows was away from China on furlough between 1871 and 1874, and between May 1895 and November 1896. After serving in China for more than fifty-two years, he died of cancer in 1914.

Sources

Broomhall, A.J. Hudson Taylor & China’s Open Century. Seven Vols. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989. Cited as “Broomhall” with volume and page number.

Broomhall, Marshall. The Jubilee Story of the China Inland Mission. London: Morgan & Scott, 1915.