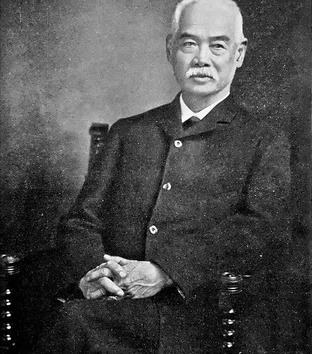

Rong Hong was born in 1828 in the village of Nam Ping, four miles west of Macao. Rong attended missionary schools in Macao and Hong Kong for eleven years. In 1847 Rong was offered an opportunity to study in the U.S. when his teacher, the Rev. Samuel Brown (Yale, 1832), returned home due to ill health. Rong attended Monson Academy in Monson, Massachusetts, from 1847-1849. He may have become a Christian there or earlier in China. While studying at Yale University from 1850-1854, he became a naturalized American citizen in 1852.

Rong returned to China in 1855 with a desire to help other Chinese study in the United States. In 1863 the Qing court began debating the option of sending students abroad. Zeng Guofan, the most influential official at that time, and Li Hongzhang, his protege, advocated sending students abroad, but many conservative officials opposed the plan. After Rong became a member of Zeng Guofan’s personal group in 1863, he was sent to the U.S. to order machinery to equip an arsenal in Shanghai and called to serve as an interpreter in 1870 during the negotiations with France in 1870. When Rong’s educational proposal was submitted to the emperor, Zeng and Li saw it as an opportunity to implement the overseas study plan that had been thwarted.

In 1871 the Throne approved the Chinese Educational Mission (C.E.M.) to the United States. Rong went ahead of the other co-commissioner, the Chinese teachers, and the students in order to establish the Mission in the United States. Rong found American families who would open their homes to two or three students and he set up the Mission’s headquarters in Springfield, Massachusetts, where the students would live during the summers in order to study Chinese. In the summer of 1872 the first group of thirty students sailed for the United States.

In 1875, while directing the Mission, he married Mary L. Kellogg, the daughter of a prominent local doctor in Hartford. Their sons are Morrison Brown Yung, who graduated from Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School in 1898 and Bartlett Golden Yung who graduated from Yale College in 1902.

Rong’s co-commissioners began writing secret reports to the Chinese Court denouncing the students for becoming Americanized and recommending that the court recall them without delay and strictly watch them after their return. The Mission continued for two more years, but the conservatives in the court grew in power. The Court recalled the Mission in June 8, 1881, six years earlier than originally planned. In August 1881 one hundred students sailed back to China.

Most students were just beginning to enter colleges when their high hopes were shattered. Over sixty percent of them had only begun their education in colleges or technical schools. Only two had completed their bachelor’s degree. Ten students refused to return to China. When the boys returned to China they were treated as criminals and did not receive the promised official ranks or high-level government jobs, but instead were paid low wages. Viceroy Li who had supported the Mission, rescued many students from obscurity by distributing them among the technical colleges in Tianjin.

In 1883 Rong Hong came to the U.S. to care for his wife, who had returned from China when her health failed. After she died in 1886, Rong found that raising his two sons helped console him in the loss of both his life’s ambition and his wife. In 1895, when Rong was recalled to China, he tried several schemes for banking or building a railroad but they failed. Then he joined other reformers in encouraging the young emperor to instigate numerous reforms during the summer of 1898, but the Empress Dowager brought that to an abrupt halt. Rong fled for his life to Shanghai and then on to Hong Kong. Though his U.S. citizenship had been annulled in 1898 as part of the Chinese Exclusion Act, he slipped by the inspector at the gangplank in San Francisco in June 1902 and arrived in New Haven in time to see his younger son graduate from Yale.

Rong went into semi-retirement in Hartford, but found he could not keep his mind off China. When Liang Qichao, a fellow exile following the 1898 reform, visited Rong in 1903 during his tour of the U.S., Rong encouraged him about the future of China. Rong died on April 22, 1912, in Hartford. He is buried in Cedar Hill cemetery.

Sources

- Stacey Bieler, "Rong Hong: Visionary for a New China," Carol Lee Hamrin, ed. with Stacey Bieler, Salt and Light: Lives of Faith that Shaped Modern China (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, Pickwick Publications, 2008)

About the Author

Research Associate, Global China Center, Michigan, USA