1811 — 1864

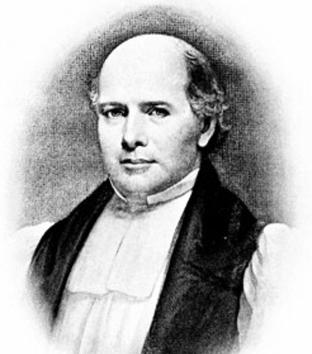

William Jones Boone

The first Episcopalian missionary bishop of China and Japan, and the first bishop of China outside the Roman tradition.

American Church Mission/American Protestant Episcopal Mission or American Episcopal Church Mission

Life

Boone was born in Walterboro, South Carolina, on July 1, 1813, descended from “an old and respectable family, some of his ancestors having held high places of trust in the civil and military government of that colony” (Stevens 7).

Already, Episcopalians had begun to awaken to their duty to take the gospel to places where Christ was not known. Under the leadership of Bishop William Doane, the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, formed in 1821, “brought about a great missionary reawakening. The Church was conceived as itself constituting the missionary society, with every baptized person a member thereof” (Huntington 13).

In contrast to the existing idea of a bishop as one ruling over established congregations, the concept of the missionary bishop, long employed in the Christian church in Europe, was revived. He would be “a Bishop sent forth by the Church, not sought for of the Church; going before to organize the Church, not waiting until the Church has been organized” (Huntington 14). William Boone would eventually become such a bishop.

After graduating with Honors from the College of South Carolina in 1829, he began to study law in the firm of Chancellor Henry William De Saussure, a noted jurist, and was admitted to the bar in 1833.

Soon, however, he was brought under the influence of evangelical preaching and, having been converted, was filled with a desire to preach the gospel of Christ to others. Over great hindrances, he resolved to give up the study of law to become a minister of the gospel. He then attended Virginia Theological Seminary, graduating in 1835, and was ordained deacon on 18 September 1836 and priest on 3 March 1837.

A great interest in world missions had already been sweeping the Protestant churches of Europe and Great Britain. In America, several young men at the General Seminary in New York had formed a missionary association. One of them was Daniel Coba of Charleston, South Carolina, who had decided God wanted him to serve in China and sought to infuse in the denomination a burden for that great nation. It was decided that he should remain at home to serve God there, but two others were accepted for service in China. They eventually settled in Batavia (Java), where they began learning the language and starting missionary work among the Chinese. One of them, Augustus Lyde, had spoken so powerfully at the Virginia Seminary, where Boone was studying, that he sensed God’s call to serve as a missionary to China. Both family and friends registered strong opposition to this idea.

When he returned to South Carolina, his bishop, Bishop Nathaniel Bowen, intended for him to remain there and offered him a prominent position in Charleston, believing that he could accomplish little in China. His sister and mother seemed to need him at home. “The idea of foreign missionaries was new to the circle of his friends” (Huntington 18). Boone’s mind, however, had been deeply stirred by a sense of his duty to those living in spiritual darkness overseas. While in seminary, “he thought he had heard a voice from Heaven saying to him, ‘Who will go for us and whom shall we send?’ so he offered himself as a candidate for missionary service.” He was resolved to follow his sense of God’s leading, despite the great pain it caused him to leave those whom he loved. Bishop Stevens says he never quite recovered from this inner wound.

To equip himself more fully for missionary work, he undertook the study of medicine at the Medical College of South Carolina, graduating as an M.D. in 1837. “He had now honorably enrolled himself as a member of each of the learned professions - law, divinity, and medicine. These professional studies, based, as they were, on a thorough collegiate course … gave breadth and solidity to his acquirements, and that intellectual force and drill which enabled him to grasp and solve the great questions and complex problems of mission-work” (Stevens 8).

Even though it had been decided that the time was not ripe to increase the number of missionaries to China, in light of his unusual qualifications and obvious dedication, he was appointed a missionary to China by the Foreign Committee of the Episcopal Church in January of 1837. During the spring of that year, he visited many churches to awaken interest in his missionary work and diffuse information about China.

That spring, he also married Sarah Amelia De Saussure, the daughter of Chancellor De Saussure, in whose law office he had served. She was “a lady elegant in her person, refined in her manners, cultivated in mind, and, like her husband, ready to sacrifice all for Christ” (Stevens 9). As with his intention to be a foreign missionary, his marriage had to overcome “intense trials of faith and patience through the opposition of friends and kindred.” His biographer, a close friend, continued, “The inner history of this period, with its mental conflicts and perplexing questions of duty, and, at times, almost despair, is one of the most touching episodes in the Bishop’s life. Often did we talk of these trials …The resulting spiritual blessings he ever gratefully acknowledged,” for they greatly strengthened his faith and missionary resolve (Stevens 9-10).

Missionary work in China

Accompanied by his wife Amelia he commenced his journey to Asia from Boston on 8 July 1837 reaching Batavia (present-day Jakarta) on 22 October the same year. There, he studied alongside the Episcopal priests Henry Lockwood and Francis Hanson to gain a degree of fluency in the Hokkien dialect of Chinese. In April of 1839, the health of both Lockwood and Hanson broke down from the oppressive climate, leaving Boone and his wife alone. “By great diligence, and amidst many drawbacks, he acquired the Chinese and Malay languages and began to use them for the diffusion of the truth” (Stevens 20).

He established schools for Chinese children. Soon he was giving both religious and secular instruction to about forty pupils. He also practiced medicine among the poor for no cost. His main goal, however, was to learn Chinese as well as possible. “A missionary’s career as a missionary – a publisher of the Gospel of grace to those who have never heard it – cannot be said to commence until he can with some fluency speak the language of the people of his adoption. This thought is a great stimulus to me. I long to be a missionary in the true and highest sense, and at present all my powers are concentrated in the effort to acquire this most difficult language” (Stevens 20).

Though he was sad that they had been left alone there, and results from his efforts were slow in coming, he did not give lose heart. Instead, he wrote, “The arrogance and presumption of being discouraged in missionary work for want of immediate success has lately been deeply impressed upon my mind … If we have any adequate view of our nothingness, and what a great and glorious thing it is to be permitted to serve our Lord Jehovah, we shall be filled with astonishment that He condescends to employ us” (Huntington 19).

He applied himself to language study with such diligence, however, that “the intense effort to master [Chinese] told … too soon upon his health; and these studies, together with teaching school, and feeling the whole responsibility of the mission resting upon him, almost broke him down before” he could reach China itself” (Stevens 21). Finally, upon the insistence of his physician, he agreed to rest from study for a while and make a voyage to Macao. While there, he realized that Macao was a better place to prepare for mission work in China. “It was in China; it was healthy; it was better fitted to carry on the work of studying and translating the language; it enabled missionaries to watch more closely the processes then going on for the opening of China, and gave them great vantage ground when such openings should take place” (Stevens 22).

Although his time in Macao did not improve his health as much as he had hoped, while there he was diligent in learning the Hokkien dialect of Chinese, and also “in perfecting his knowledge of the Chinese classics, in which he obtained, according to the testimony of those best competent to judge, marked superiority” (Stevens 22). Despite poor health, he persisted, and sensed great happiness in his work.

The main discouragement was the lack of sympathy for his mission among church people at home. In fact, the mission board almost decided to terminate the mission because of lack of results, but finally decided to wait in faith for God to produce fruit.

As a result of this visit, prior to the conclusion of the First Opium War, Boone relocated to Macau in 1840. In February 1842 conditions in China were considered secure enough for Boone to relocate his missionary work to Kulangsu, a small island half a mile from the recently opened treaty port of Amoy (now called Xiamen), to set up the first base for the Episcopalians within China proper. He and his wife arrived there in June of that year, “accompanied by Mr. and Mrs. MacBryde and Dr. William Henry Cumming” (Wylie 99-100). They joined David Abeel, who had already planted a church there. Since Hokkien was spoken there, he could commence work immediately. He continued to call for more missionaries to be sent to join him, but the response was silence.

In August of 1842, his wife died after five years of happy marriage and close collaboration in the work. He wrote that “she was the most energetic missionary that I have ever met in my five years’ sojourn in the East” (Stevens 25).

She was the first female missionary who died in China, and her body was laid to rest in a grave in the island of Kulangsu [now called Gulangyu] … In her last sickness she begged her husband to say to her friends that though her missionary course would be short if she died from her present disease, that she never had, nor did she now, regret coming out as a missionary. “No,” she added; “if there is a mercy in life for which I feel thankful to God it is that He has condescended to employ me as a missionary to the heathen.” Though cast down by this affliction, he was not destroyed. “I trust the Lord is sanctifying my affliction to me; I feel more determined than ever that by His grace I will live and die in His service in China” (Stevens 25).

The death of his wife made it necessary for Boone to return to the United States with his two young children in February 1843. The Foreign Board also desired that he seek to “rouse up the Church to a sense of its duty to over three hundred millions” of non-Christians in China (Stevens 26). He reached New York in the summer of 1843, put his children into the care of people whom he trusted, and set out to pass on the burden of bringing the light of Christ to the Chinese. His efforts were notably effective, as he spoke in churches from Boston to New Orleans.

His addresses were simple but effective; eloquent, without oratory; powerful, without pretension; telling the story of his work and of his field with an unction that showed his heart was in it, and communicating to others the deep emotions which often stirred the depths of his own soul. It was a great blessing to our whole Church to be brought into contact with this good man; you became insensibly interested, first in him, then in his work. He was a noble embodiment of missionary zeal, guided by knowledge and tempered by discretion; and fitly illustrated the Church’s idea of a single-hearted, single-eyed missionary of the Cross (Stevens 26-27).

While he was in the United States, the Episcopal Board of Missions decided that, if they were to adhere to episcopal ecclesiology, the mission in China must have its own bishop. The General Convention passed a resolution to this effect in 1844 and appointed William Boone to be bishop to China.

The Doctor of Divinity degree was also conferred upon him in 1843.

Boone was consecrated at St. Peter’s Church, Philadelphia on 26 October 1844 as the first Anglican missionary bishop of China and Japan (under later bishops, the missionary district was reduced and called Shanghai) and the first bishop of China outside the Roman tradition. Among ten other bishops, the official Consecrators were Philander Chase, George Washington Doane, and James Hervey Otey. (In Roman, Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican traditions, each bishop must be consecrated by three other bishops who stand in a direct line of episcopal succession going back to the early church.) William Jones Boone was the 45th bishop consecrated for the Episcopal Church.

While at home, he also married Phoebe Caroline Elliott, the sister of Bishop Stephen Elliott of Georgia (1806-1866).

Influenced by British CMS missionary George Smith, he chose to relocate the center of his mission work to Shanghai in 1845, because of its closer proximity to Beijing, healthier climate, strategic location as a major port, foreign protection, and easier access to the people.

Establishing a new mission in China

When they sailed for China in December 1844, they took with them a party of new Episcopal missionaries: the Revs. Henry W. Woods and Richardson Graham, Mrs. Woods, Miss Emma Jones, and a Miss Morse. During the journey Boone taught the others Chinese, assisted by a Chinese passenger. By the end of the trip, the new workers had already learned 1,200 Chinese characters. They arrived in Hong Kong in April and proceeded immediately to Shanghai. Under the provisions of the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, they were now allowed to teach Christianity anywhere in China, and Chinese were permitted to profess the Christian faith.

On the threshold of this new missionary enterprise, Boone wrote, “I stand prepared to throw my whole heart, and life, and soul, into the effort to make known the precious Redeemer to these perishing millions” (Stevens 34).

Since land in the city was very expensive, he chose to settle on the north bank of the Suzhou (Soochow) Creek outside the Foreign Settlement where British lived. In effect, he set up a new American settlement, which cooperated closely with the British.

His biographer sums up the various works which Boone and his coworkers accomplished over the years:

Schools were established. Translations of the Catechism, Prayer Book, and other simple religious works were prepared by the Bishop. Preaching and distributing of tracts were kept up on the surrounding villages… . He was active in getting up Trinity Church for the English and American residents, and in procuring a Colonial Chaplain from England. He early planned, and soon saw built, a large schoolhouse, which, for some years, served as a boarding-school for boys, and a home for the missionaries. Also, a house for the girls’ school. He built a church, the first Protestant church in China, in the very centre of the city of Shanghai, and another smaller one near the residence of the missionaries… . He had the whole machinery of the mission under his eye, and regulated it with a wise mince and a judicial hand (Stevens 34-35).

The schoolhouse was completed in July 1849, constructed on high ground along the river away from the center of the city. Mrs. Boone wrote: “It is 120 feet long and one hundred feet deep, to the end of the wings which run back. Upper and lower verandas and plenty of room for everybody, all built of brick and plastered outside and in” (Huntington 34). About 100 people were crowded into the premises at first, while other structures were built. A house for the Boones allowed them fresh air and sunshine, so that the health of Boone and their son William (“Willie”) improved substantially.

The school building had a chapel that could hold 300 people. Boone himself literally drummed up attention for worship services by going about with a great gong and beating on it before services. Soon, conversions took place among the students. Mrs. Boone wrote, “The first converts were sincere and earnest” (Huntington 36).

Missionary methods

Rather than scattering the seed of the gospel far and wide, Boone set a policy of “working with small groups intensively, building up a solid membership of carefully instructed Christians … From the earliest beginnings in Shanghai use was made of rented buildings on busy streets where a native evangelist or missionary was host to any inquirers who cared to enter, to question, to discuss, and to learn” (Huntington 43). And, rather than trying to reach all of China, he decided to expand the mission out from Shanghai and up the Yangzi River, so that all his workers and converts could have relatively easy communication with each other. Aside from one abortive attempt to begin a work in Yantai in 1861, he and his successors adhered to this general strategy.

Frustrations and challenges

Aside from the difficulty of the language, discomforts of living in China, and the disappointing slowness of response, Boone and his colleagues faced the constant need for more workers. When asked what were the trials faced by missionaries, he wrote, “To see so much needing to be done, the field so open, the preparation so arduous, and the prospect of others joining us so faint; this constitutes our greatest and most constant trial… . How can we be successful and the work well done when one man is left to do the work which it would take two or three men to do properly?” (Huntington 45).

The Delegates’ Bible

By this time, the need to revise the translation of the Bible by Robert Morrison and William Milne had become apparent to almost all the missionaries. In 1847, a committee of delegates from several mission societies was formed, all men recognized for their outstanding grasp of Chinese as well as the biblical languages: Elijah Bridgman, John Stronach, Walter Medhurst, Walter Lowrie, and Boone. Almost immediately, they confronted the question of which Chinese word was most appropriate to translate the Hebrew and Greek terms for “God.”

He advocated using the word shen 神, in opposition to figures like James Legge who favored using Shangdi 上帝. He reasoned that Shangdi was the name of the chief deity of the Chinese, one among many, whereas shen, like Elohim and theos, referred to “gods” generically, and could thus also be a title for the one true God, as those Greek words had been employed in the Septuagint (the translation of the Old Testament into Greek) and in the New Testament. Shen has almost the same semantic range as theos; its distinction from false “gods” and idols could easily be made clear by its use in context, as was the case in the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament.

Boone threw himself fully into this controversy, despite ill health that had forced him to cease from preaching. He wrote:

In my opinion, this is the most important emergency in which I have been placed for advancing the true interests of the Christian cause in China. An error on this point will do more to retard this people’s coming to a knowledge of the true God than on almost anything which could be mentioned. It is in vain to fight against Polytheism in the name of a heathen deity [Shangdi]; we must use the generic term for this reason, if for no other, namely, that Jehovah does not propose himself to a Polytheistic nation to take the place of their Jupiter or Neptune, but in place of the whole class [of deities]. We must therefore give Him the name of the class, and affirm that He alone is entitled to the name” (Stevens 36).

To defend his views, in 1848 Boone issued a treatise that discusses the issue in great detail: An Essay on the Proper Rendering of the Words Elohim and Theos into the Chinese Language. He later wrote two responses to rebuttals from those who advocated Shangdi as the proper translation for “God”: Defense of an essay on the proper rendering of the words Elohim and Theos into the Chinese language (1850); and A vindication of comments on the translation of Ephesians 1 in the Delegates’ version of the New Testament (1852).

For the main arguments of this long and learned treatise, see the appendix after the Resources section below.

The Delegates’ Bible was a translation into literary Chinese. Boone withdrew from the work early because of his disagreement with those who advocated the use of Shangdi. In addition to that work, in the next few years Boone, with a Mr. Keith and others, also translated Matthew, Mark, John, Romans, and parts of the Old Testament, as well as a catechism, morning prayers, and church prayers, into the spoken language of Jiangsu, the dialect used in Shanghai and its environs, which had hitherto not been reduced to writing. “He succeeded most admirably, and thus was the first to render the Word of God into the mother tongue of a population larger than is contained in all the United States. The amount of literary labor and critical knowledge required for this work cannot be fully known or appreciated by us” (Stevens 38).

Ordaining the first Chinese deacon (of the Episcopal denomination)

On his trip home, Boone had taken with him a young man whose name was Huang Guangcai (Wong Ji; Wong Kong-chai; “Chae” in his biography, 1827–96) in 1851. By the time of their return to China in 1844, Chae had learned the English language. On the voyage, Mrs. Boone spent a great deal of time teaching him about Christianity, and he had been deeply impressed. Boone later carefully instructed him and, after a period of probation, baptized Chae and admitted him as a candidate for ordination. The ceremony took place in Shanghai, with the sermon being preached by a member of the English Anglican mission. The novelty of it drew a large crowd of Chinese, both Christian and non-Christian, as well as foreigners to the church at the center of the city.

This act of cooperation between British Anglicans and American Episcopalians presaged the later very cordial collaboration between Boone and Bishop George Smith, the Anglican prelate in Hong Kong who also had jurisdiction over Anglicans in the five “treaty ports” of newly opened China.

“For years [Huang’s] influence brought many to the love of God and His Church, through his work as priest-in-charge of the Church of our Saviour” in Shanghai. ‘It is no exaggeration,’ the Rev. F.L. Hawks Pott said, later, ‘that if Bishop Boone had accomplished nothing more than to lead this one man to become a disciple of Christ, his life would not have been spent in vain, for the influence and work of Pastor Wong has been rich and wide in its results’” (Huntington 37).

In 1848, one candidate presented for baptism was a young man eighteen years old whose name was Yen Yung-Kyung, “who became a great Christian leader. The rare quality of the first Chinese priests was an indication of Bishop Boone’s wise emphasis on Christian education” (Huntington 37). Boone laid great stress on regular daily catechetical instruction as the best means of instilling Christian truth into seekers. He tried very hard to “test the sincerity of those who have come before he receives them into the Church” (Huntington 37). Clearly, he believed in laying a solid foundation, more than in scattering seed far and wide and baptizing people without careful examination. Most missionaries of that era followed the same procedure. Results may have seemed slow, but growth was solid.

In 1851 the girls’ school building was completed, to train future wives for the students in the boys’ school. One of the first students later married the Rev. Huang Guangcai and became noted for her humility and moral courage. This school later became known as St. Mary’s Hall, which “deeply permeated Chinese society with wives and teachers and nurses” (Huntington 40).

Though Boone naturally concentrated his efforts upon his own mission, like others he was always ready to encourage workers of other agencies. He opened his home to new arrivals or those in transit, as well as to members of other societies living in Shanghai, including the young Hudson Taylor.

Furlough and return

Boone was very feeble at the time but filled with joy at this great step forward in his mission to plant a fully Chinese church. The health of both him and his wife had deteriorated so much by 1852 that they had to return to the United States again to recuperate. The great Taiping Rebellion took place while he was home. Shanghai was captured, but worship services continued, except in the rebel-occupied Chinese city. At first, the semi-Christian nature of the Taipings gave promise of the advance of the gospel in China. Boone very much wanted to return to witness and evaluate these developments. He brought three assistants with him this time. He found Shanghai in total chaos ravaged by war with all its attendant evils and suffering. Even worse, he discovered that the Taipings were so heterodox in their teachings, and the leader, Hong Xiuquan, was guilty of radical self-exaltation and, in the eyes of most missionaries, idolatrous blasphemy.

Despite all the obstacles, and in very poor health, Boone kept up a full schedule of ministry under chaotic conditions until, in 1857, he was once again compelled to return to the United States to rest. He settled his family in Orange, New Jersey, and slowed his pace, but his mind remained actively involved in the events taking place in China and Japan. In 1858, he urged the Foreign Committee to open a missionary work in Japan. Also in 1858, the American minister in China was able to negotiate a treaty with the emperor of China that allowed not only trade and diplomatic relations, but protection to Christian missionaries and their converts throughout the empire. Bishop Boone responded to this breakthrough by calling for more missionaries to go to China.

His efforts achieved their intended goals. In 1859, Japan was designated as a mission station, and placed under his jurisdiction, with two of his missionaries, Williams and Liggins, assigned to work there. The Foreign Committee also resolved to send out more workers to China and authorized Boone to recruit them. Episcopalians responded with enthusiasm, so that when in 1859 he and Mrs. Boone once again set sail for China, twelve new missionaries, both men and women, went with them.

Renewed ministry in China

Although the Convention of 1860 had granted unlimited access to foreigners to live and work in China, the cost was high. Chinese could never forget the humiliation of defeat in the Opium Wars or the sacking of the Summer Palace in Beijing. Missionaries were willing to take advantage of the opportunities granted by the treaties, but they were open in their criticism of both the opium trade and the violence exercised by Western powers. “Bishop Boone lamented what he called American aggression, for although the United States took only a small part militarily, she was firmly on the bandwagon [of Western expansion in China] in the person of her Plenipotentiary, the Hon. John E. Ward in Peking” (Broomhall, If I Had a Thousand Lives, 240). Still, when the British “Admiral Hope ‘formally opened the great river’ in 1861, … with the admiral travelled a number of diplomats and missionaries as guests or assistants to the national delegations … Representing Bishop William Boone was … his outstanding young assistant, Samuel Joseph Schereschewsky,” who would later become Bishop of Shanghai (Broomhall, If I Had a Thousand Lives, 262).

Upon his return, Boone encountered a variety of challenges and trials. When the British chaplain to Shanghai died in April 1862, he naturally supplied his place until the following spring. The situation in his mission taxed him to the full. First, he had to degrade from the ministry a man named Tong, whom he had ordained as the second Chinese deacon.

Then followed the gradual dismemberment of the mission, by death, and removal of many of its members; then the disbanding, for lack of funds, of the boys’ school; then the giving up of the Northern Mission to Chefoo [Yantia]; and the declining health of Mrs. Boone. All these sad things fell like trip-hammer blows upon the Bishop’s heart, and almost crushed out its hope and life. But he still hoped against hope [Romans 4:18], feeling that the cause was God’s, and that He would not forsake the vine of His own planting (Stevens 50).

He was now left with only three missionaries, and Deacon Huang, whom he advanced to the priesthood [i.e., status of presbyter] in November 1863.

But his wife’s health became so bad that he decided to take her to Singapore and then Egypt, hoping that a better climate would help her. It was all to no avail, however, and she died in a hotel at the Isthmus of Suez, with only her husband, her son, and a Chinese servant at her side. She was buried on an island in the Red Sea, her husband reading over her the burial service from the Book of Common Prayer.

Boone then took his youngest son to Germany, where, as his wife had requested, he placed him in the care of a Miss Jones, who had long been her friend and fellow missionary.

He then proceeded back to Singapore. On the way, the ship was nearly wrecked in a terrible typhoon, and then “ship fever” and smallpox broke out among the crew and passengers. “In the midst of all this danger and alarm the Bishop bore up as a Christian hero, calming the excited, comforting the despairing, lending himself to every effort that could encourage hope or impart consolation; and, when the storm abated, and the dangers were over, he held a thanksgiving service on board” (Stevens 51).

He reached Shanghai in June, very weak but in good spirits. A month later, however, his body, worn out by strenuous labor, grief, the trials of his last voyage, and illness, gave out, and he died on July 17, 1864.

Character

Even allowing for the conventions of Victorian eulogies, the description of his character by his friend Bishop Stevens deserves to be quoted at length:

In all his relations to his own and to his mission family, he manifested that unselfishness, simplicity, gravity, godliness, and wisdom, which surrounded his character as with a halo of grace and beauty.

His love of his missionary work was intense. From the time that he gave himself to Christ for service in [foreign] lands, to his death, he never faltered in his zeal and perseverance, never tired of the work; but, with an ever-growing consciousness of the importance of it, he gloried in spending and being spent in the holy service. He wandered off into no side-paths. He had no by-ends to serve. His eye was single; his aim was single; and guided by faith, nerved by hope, impelled by love, he pressed toward the mark for the prize of his high calling, ever looking unto Jesus …

Unquestioning belief in God’s word, unfaltering obedience to God’s command, unwavering hope in God’s promises, and unfailing love to God, were the controlling elements of his life, and made him an eminently faithful missionary, and an eminently godly man. So intensely active was he, even when, by reason of sickness and debility, he might well claim repose, … that, when unable to preach, he would place one of the missionaries, or the native Deacon Chao, in the pulpit, while he would stand at the street-gate and ask the people, as the passed by, to “turn in and hear the doctrine of Jesus,” declaring that “he had rather be a door-keeper in the house of God than be altogether laid aside.”

With all his zeal and ceaseless activity, he yet had the most humble idea of his own labors. He often spoke of himself as being a useless member of the mission, … holding on to a place which another could easily fill; and this greatly distressed him (Stevens 52-54).

His second wife wrote that “Dr. Boone is the most wonderfully and uniformly cheerful person I ever saw” (Huntington 36). After his death, a newspaper in the United States said that “Our Bishop there was a man of the loveliest personal character and of ascetic sanctity” (Huntington 40).

The minutes on his death in the records of the Foreign Society gave this description:

He was a scholar of mature general learning. As a Chinese scholar he had probably few superiors among the foreign students of that difficult language… . His whole mind was singularly adapted to be the umpire in contested questions and the administration of conflicting interests. He was remarkable for his distinctness of perception and his moderation of statement. He was adorned with the most transparent candor and elevated above all inferior and selfish ends. No good man could associate with him without pleasure, and every intelligent man derived profit from his conversation. His temper was genial and benevolent, and his example was pure and lovely. He gathered around him the warmest devotion of missionaries and the most filial affection and confidence of the Chinese. Perhaps few men have every lived against whom so little was said and with whom so little personal fault was found by his associates. His personal religion, though wholly without forthputting of pretense, was so distinct, so positive, so truly holy as the work of the Holy Spirit of God, that it compelled equally the veneration and the confidence of those who knew him.

The Foreign Committee recognized him as a “man of strong intellectual power … He was possessed of a large measure of practical good sense and sound good judgment… often exhibited in circumstances of greatest delicacy and difficulty” (Huntington 40-41).

Legacy

William Jones Boone was pre-eminently a founder. Starting from nothing, he laid the foundations of the American Episcopal mission, with the first baptism, the first Christian marriage, the first church building, the first celebration of Holy Communion, first confirmation, first ordination of a Chinese Episcopal deacon, and the first ordination of a priest (presbyter), Huang Guangcai (黃光彩). Boone was responsible for the recruitment of numerous missionaries; notably Emma Jones, Henry M. Parker, and Channing Moore Williams, his eventual successor as Bishop of China and Japan. In addition to his work on the Delegates’ Bible, Boone with others is credited with the translation of the Book of Common Prayer into Chinese.

His own life and example may have been his most lasting contribution: “Bishop Boone was … one of the great Bishops of the Church in any land. Devout, farseeing, steady, he set a lofty standard for all who followed. Indefatigable, magnetic,” he drew money and recruits to himself and fueled a lasting commitment of the Episcopal denomination to China (Huntington 23).

Huachung (Huazhong) University, whose English name was Central China University, was originally called Boone University, after Bishop Boone. Bishop Boone Road in Hong Kong and Boone Divinity School, which was opened in 1906, were also named after him.

Family

Boone’s first son, also named William Jones Boone (1846-1891), also served as a Missionary Bishop of Shanghai in the Episcopal Church. His second son, H.W. Boone, M.D., did medical work for the Protestant Episcopal Church in Shanghai.

Bishop Stevens wrote of Boone, “The man, and his work, are both remarkable - the man, as possessing qualities of heart and mind which would have given him eminence in any field; and the work, as being the nearest in character to that of Him who left the abodes of Heaven that he might seek and save the lost on earth” (Stevens 6).

Works

(1837) Address in Behalf of the China Mission, By the Rev. William J. Boone, M.D., Missionary of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States of America to China.

(1848) An Essay on the Proper Rendering of the Words Elohim and Theos into the Chinese Language. Canton [Guangzhou]: Office of the Chinese Repository.

(1850) Defense of an essay on the proper rendering of the words Elohim and Theos into the Chinese language. Canton [Guangzhou]: Office of the Chinese Repository.

(1852) A vindication of comments on the translation of Ephesians 1 in the Delegates’ version of the New Testament. Canton [Guangzhou]. Publisher not indicated - presumably Office of the Chinese Repository.

He also contributed to the Chinese Repository articles on the astronomy and on Long Measure of the Shu Jing.

Appendix: On the proper Chinese word for “God”

In general, Boone argued that we must use a term that guards against polytheism. The question is whether we should use the name of the highest being worshiped by the Chinese, or a general term for the highest class of beings (“gods”) worshiped by them.

The example of the writers of the Old Testament and New Testament must be our guide. They also lived among polytheistic societies. They did not select a name for God from any of the other religions but used a generic term to designate the entire class of “gods.” In Hebrew, Elohim, and in Greek, theos, referred to the class of beings worshiped, that is to say, “gods.” In Chinese, that would be shen.

Secondly, if we substitute a name of any particular deity, some passages of the Bible will not be clear prohibitions against polytheism. “You shall not have any other God besides (before) me,” for example. If we use a name (Boone chose Jupiter for the Romans), that would only prohibit the worship of any other god named Jupiter; you could worship another god with another name if you wished.

He notes that Roman Catholics had chosen “Tian Zhu,” “Heavenly Lord,” which thereby allowed for the worship of Mary and the saints. Among Chinese, it allowed the worship of Shang Di as they understood him, and this was used as an excuse by some not to convert to Christianity, since, they claimed, they already worshiped the same God as did the Christians.

Further: There is only one true God. The idea of many “gods” arose only because of pagan polytheism. In reality, “God” should be applied to only one being, the true God of the Bible. Thus, using Shen excludes the worship of all other so-called “gods” of the Chinese pantheon.

Then Boone responds to the claim that, in addition to celestial beings called shen who received worship, there was another group of them, called “di” (or, Ti, in his Romanization). But, surveying classical literature, he finds that there was no class of di separate from shen. The ancient Chinese rulers appointed officials to organize the worship and rites to honor “gods” (shen) and men. In other words, they offered ceremonies to honor only two classes of beings, shen (gods), and humans.

This bears on whether Shang Ti (Di), the name proposed by those who opposed the use of Shen, is one of the shen or whether he belonged to another class, that of di, as the highest of them.

He quotes passages that refer to Shang Di among the shen to be worshiped, proving that he was of the same class as they. He is worshiped as “the God of Heaven” (Tian Zhi Shen), showing that Shang Di is one of the “gods” (shen), albeit the highest.

Boone goes on to show that these shen were the highest beings whom the ancient Chinese worshiped, and that the highest, Shang Di, was one of them. He cites ancient texts on ritual that divide objects of worship into three groups: celestial gods (shen), the spirits of departed men, and gui, “ghosts.” There was no fourth group, di, whom they separately worshiped.

Furthermore, the generic word shen could be applied to all objects of worship, including the spirits of departed humans, i.e., ghosts. Ancient texts also refer to “national gods,” using the word shen. Ancient sources also divide designate all rituals as those for “gods and men.”

He concludes that shen is therefore the best term to refer both to the highest beings honored by Chinese with sacrifices and to all spiritual beings.

As such it corresponds to the Greek word theos in pagan literature and in the New Testament, as well as in the Greek translation of the Old Testament (the Septuagint).

Boone then proceeds to demonstrate that when the Chinese referred to Heaven as the highest object of their worship, they identified this being with Shang Di.

He also reminds his readers that, prior to 1847, no dictionary or Bible translation done by missionaries used Di as a name for God. And they all use shen to refer to “gods” worshiped by the Chinese or pagans in biblical times.

Of course, Boone knows the objections to the use of Shen and deals with them.

First: None of the attributes of the highest god worshiped by the Chinese, Shang Di or Heaven (Tian) are predicated of a shen. He replies that, as he has demonstrated, the highest god of the Chinese belongs to the class of shen, and therefore all attributes predicated of their highest god are applied to a being who belongs to the class of shen. Thus, shen may properly be applied to their highest God.

Second: The Greeks and Romans were polytheists, but some of their philosophers used the word theos to refer to a supreme framer and governor of the universe, who resembled the Chinese Shang Di. Boone replies: Yes, that is true, and it was a step towards monotheism, but the writers of the New Testament and Septuagint, knowing this, took the word theos and then, by context, made it clear that there was only one Being who deserved this name, the Creator God revealed to the Hebrews and then the apostles. In other words, they more narrowly defined theos, when used as a name for the Supreme Being, to designate a Being who was the sole member of his class, namely, the only true and living God. We can and should do the same with Shen.

Furthermore, since the Chinese did not use Shen to refer to any being who created and governed the universe, those missionaries who object to that name for the biblical God argued that we should not, either. Boone replies that we must not limit our use of their language to their limited knowledge of the truth but should, like the writers of the Bible, take an existing word and invest it with a new and true meaning.

Third: In Chinese medical literature, shen is sometimes referred to the spirit or divine element in men. Boone admits that fact, but responds that context determines meaning, and that biblical contexts will make clear that the Being to whom the name Shen is applied is the unique Creator and Governor of the world.

Next Boone seeks to demonstrate that the word Di (Ti) cannot be used to translate Elohim or theos.

It was never a name for any particular deity or person worshiped or honored by the Chinese, but always a title applied to an individual. It could mean “judge”; or “ruler” (divine or human), including the greatest of these, Shang Di, the Ruler on High, who reigned over the “five rulers” (Wu Di) who were inferior to him; “emperor.” When used with reference to one individual deity or human, it means something like “king,” as in “King David,” “King” being his title and not his proper name.

Furthermore, when shen, huang (as in Huang Di, Emperor), and di are ranked, shen is the highest and di is the lowest in rank.

In short, di “is a relative term, designating an office, and not an appellative term” [that is, a name] (60).

Boone then points out the insuperable difficulties of using Shang Di in many passages of Scripture. For example, “You shall not have any other gods besides me,” would forbid citizens of China from having any other ruler than Shang Di – that is, they could not honor the emperor.

Also, that commandment would not forbid the worship of the multitude of gods -shen - worshiped by the masses of the people of China.

The above summary of Boone’s Treatise does not do justice to the detailed nature of his argument, or the many passages from Chinese and foreign writers illustrating the meanings of the words involved.

Clearly, Bishop Boone had both a general and a specific grasp of Chinese classical literature and employed this to make his case for using Shen to translate Elohim and theos.

G. Wright Doyle

Editor, Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity

Sources

Bays, Daniel. “Boone, William Jones, Sr.” In Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. Edited by Gerald H. Anderson. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1988, 77.

Broomhall, A.J. Hudson Taylor & China’s Open Century. Seven Volumes. Sevenoaks: Hodder & Stoughton and Overseas Missionary Fellowship. Book One: Barbarians at the Gates, 1981; Book Two: Over the Treaty Wall, 1982. Book Three: If I had a Thousand Lives, 1982. Republished in two volumes with the title, The Shaping of Modern China: Hudson Taylor’s Life and Legacy, by Piquant Editions and William Carey Library, 2005.

Covell, Ralph R. “Boone, William Jones, Sr.” In A Dictionary of Asian Christianity. Edited by Scott W. Sunquist. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001, 90.

Huntington, Virginia E. Along the Great River: The Story of the Episcopal Church in China. New York: National Council of the Protestant Episcopal Church, 1940.

Cui’an Peng. “Huang Guangcai.” Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity(https://www.bdcconline.net/en/stories/huang-guangcai).

Stevens, Wiliam Bacon. Memorial Sermon on Bishop Boone: A Sermon Commemorative of the Life of the Rt. Rev. William Jones Boone, D.D. Missionary Bishop to China. Philadelphia, PA: Sherman & Co., 1865.

Wikipedia article, William Jones Boone. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Wiley, Alexander. Memorials of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese. Shanghai, American Presbyterian Mission Press, 1867. Republished by Andesite Press, and imprint of Creative Media Partners.

For information about William Jones Boone, go to https://researchworks.oclc.org/archivegrid/collection/data/655269264.

Wikipedia: Huachung University: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huachung_University. Accessed May 1, 2024.

See also

Wickeri, Philip Lauri (2015). Christian Encounters with Chinese Culture: Essays on Anglican and Episcopal History in China. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789888313259. OCLC 911961991.

"Anglican and Episcopal Bishops in China, 1844–1912" (PDF). Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui Archives. May 11, 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 4, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

"China, Missionary District of". An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church. 2000. Archived from the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

Gray, G. F. S. (1996). Smalley, Martha Lund (ed.). Anglicans in China: A History of the Zhonghua Shenggong Hui (Chung Hua Sheng Kung Huei). Episcopal China Mission History Project.

About the Author

Director, Global China Center; English Editor, Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.