1892 — 1991

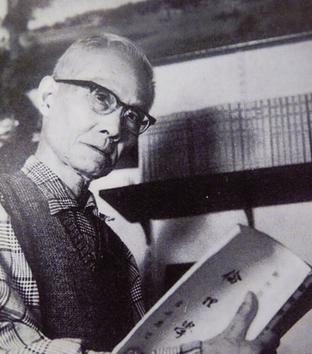

Xie Fuya

Chinese Christian thinker, philosopher, writer, translator. Taught at several universities and produced many original writings and translations.

Part One: Life

Xie Fuya (known also as Zin, and Zia) was born June 29, 1892, in Shanyin County of Shaoxingfu, Zhejiang Province, the second child in his family.At the age of thirteen, he was named Fuya by one of his uncles. While studying in Japan, Xie Fuya took the name Nai Ren. His English name, Nai Zin Zia (abbreviated as N.Z. Zia) is based on a transliteration of “Xie Nai Ren”).

His father, Xie Changqu was a Xiucai (scholar with Master degree) in late Qing Dynasty who taught students in his home. When Xie Fuya was two years old, his father became ill and died early. The only impression Xie had of his father was of sitting on his knee, while he corrected essays. His mother, widowed at the age of 27, brought up four children with the greatest difficulty. Even amidst these trials, she walked around in rooms and recited Buddhist scriptures, crying out for help from Buddha .Her labors, sorrowful countenance, and her devotion left an indelible impression upon Xie Fuya. He later felt that his mother’s devout religious attitude had sown a seed deep in his soul.

Both of Xie’s parents came from very distinguished families. Though in his youth his family was relatively poor after his father’s death, by selling and pawning old possessions and the help of his maternal uncle they were able to make ends meet, though just barely. Coming from a family which for generations had been literary, at the early age of four Xie was already receiving a formal, systematic, and rigorous traditional education, studying for half a day each day. At five, he began an all-day curriculum that lasted fifteen years. Beginning with the Three Character Classic, the Book of Odes, Analects, Mencius, Great Learning, Doctrine of the Mean, and then progressing to the Erya, (or Ready Guide, the first extant Chinese dictionary with glosses and classical texts), the Book of History, the Yi Jing, Book of Rites, Spring and Autumn Annals. Next came lessons in Chinese, national policy, The Records of the Grand Historian, and other classics.

From childhood, Xie was able to learn easily. Xie enjoyed the benefits of this training in traditional Chinese culture for the rest of his life. It became the foundation of the structure of his system of thought as he expounded the relationship of Chinese culture and Christianity.

In 1905, at the age of thirteen, Xie took the county level examination, but didn’t pass. Even after ten years of hard study, he had not been able to realize his dream. The next year, after the imperial examination system had been abolished, he took the test for the Shaoxing School of Chinese and Western studies and received the highest score. He couldn’t afford all the expenses, however, and had to give up this opportunity. In the same year, having gone to Jiangsu with his maternal grandfather, who had taken a position as legal advisor, Xie studied law from him. With the doors to the school of Chinese and Western studies closed, and the imperial examinations abolished, Xie thought he would try the study of law in order to get a stable job or perhaps even find a position as a teacher in Shaoxing. Sadly, however, his grandfather was addicted to opium, and was not adept at training the younger generation, but threw away his job and returned home, Xie lost his own livelihood, having wasted three or four years of his youth. He later wrote a poem mocking himself, “Unsuccessful at both regular education and at law.”

At the age of eighteen, Xie went to live with his uncle, to help him writing the history of the Xie family. His arrival just happened to coincide with the death of his aunt. While he was helping with the preparations for the burial, he encountered his distant cousin Xie Naiji, who had just returned on vacation from studying in Japan. As they conversed, his cousin was moved to learn that the way ahead for such and intelligent person with literary talent was blocked by poverty. He therefore urged Xie Fuya to go to Japan for further study. At the beginning of 1911, Xie went to Suzhou to borrow three hundred thousand dollars from his aunt to go to school in Japan. He then took a ship from Shanghai to Yokahoma. After a month at sea, he arrived in Japan, and stayed for a while at his cousin’s home in Tokyo. While in school, his expenses were met by his cousin. Xie Fuya’s life had taken a decisive turn for the better.

Soon after arriving in Japan, Xie enrolled in language school to learn Japanese. After completing advanced elementary training, he registered for admission to the Tokyo Classical Education Institute. While there, he was elected as president of his class. In March, 1912, he graduated from the institute, having received the first academic diploma of his life.

In order to prepare for the admission test for the Japanese Institute of Higher Learning, which would be funded by the government, Xie moved to a dormitory run by the YMCA for overseas Chinese students near Waseda University. This was his first real encounter with the Christian faith. During this time, he became best friends with Ma Boyuan, who belonged to the Waseda chapter of the YMCA, and as a result got to know a number of other Christians as friends. Among them, the deepest impression upon Xie was made by the hymns sung by his classmate Luo Wenguang. He was often deeply moved by these songs, which reminded him of his mother’s religious piety. In 1913, he contracted a virulent case of tuberculosis. The doctor told his friend Luo Wenguang that Xie had only three months to live. Luo didn’t tell Xie, but went with him to the seashore for more than a month for rest and recuperation. Afterwards, his tuberculosis spontaneously disappeared, leaving only a tiny speck of a calcification on the X-ray image.

In April, 2014, Xie was admitted to the Tokyo Higher Normal Institute, having qualified for a national scholarship. Because he cheated on a test, however, the young Xie was disciplined with expulsion from the school. With the help of his friend, in the fall of 1915 he transferred to a Christian institution, Rikkyo University. During this time, his eyesight suddenly deteriorated, and the doctor diagnosed him with acute epiploitis, which later became chronic. The doctor recommended that he not continue with his education, but Xie insisted that he would not stop. During his treatment, a nurse injected him with the wrong medication, and begged on her knees or his forgiveness. This experience made Xie suddenly feel God’s kindness and mercy, and caused him to recall the image of a time in his youth when his mother prayed for blessing for his younger brother, who lay in bed ill. Meanwhile, the sound of his friend Luo Wenguang playing Christian songs produced in him a yearning to convert to Christianity.

In the spring of 1916, accompanied by Luo Wenguang and Zheng Tianmin, he was baptized by an American clergyman in Trinity Episcopal Church, and formally became a Christian. Looking back many years later, he saw his baptism as a random event, the result of “plucking a ripe fruit,” because his being touched by the character of several Christian friends was inseparable from the influence in his heart of his mother’s piety.

After his baptism, Xie often went to church for worship, other meetings and evangelistic events. At one evangelistic meeting, he met Pastor Ding Limei, who had come to Japan to preach. Ding, who was serving as Evangelistic Secretary of the Chinese YMCA Student Volunteer Movement, heard that Xie Fuya’s writings were rich in literary grace. He tried his utmost to urge him to return to China and engage in literature evangelism. Ding’s suggestion made Xie realize that this was an excellent opportunity. He really did possess literary talent, having already contributed many articles to various periodicals during his stay in Japan. Now, because of illness he could not continue his studies there. He followed Ding’s advice, therefore, and in the fall of 1916 concluded his time in Japan.

Upon his return to China, he began literature work for the National Committee of the YMCA of China. He edited “Co-Workers” and other magazines, wrote the annual report of the work of the China YMCA, and contributed articles often to “Youth Progress” and other publications. In 1917, he translated Harry Emerson Fosdick’s Comments on the Meaning of Prayer and The Manhood of the Master, Francis Bacon’s Essays, and other works.

In the fall of 1918, Yu Rizhang, the General Secretary of the YMCA, transferred Xie to the General Administration of the YMCA and put him in charge of literature work. As Chinese secretary for Yu, Xie devoted his energies to helping the YMCA, by taking part in fund-raising and all sorts of social service activities, and coordinating the work of the YMCA in various locations. At the same time, the spirit of an energetic pursuit of progress and mutual cooperation within the YMCA exerted a profound influence upon Xie’s knowledge and character. He later thought that this period of work with the YMCA was the time most unfettered by entanglement in personal matters and the happiest of his entire working career, and was the first high point of his life.

As a result of Xie’s performance, in 2915 Yu Rizhang offered to him the opportunity given by the North American YMCA to go overseas to further his studies, sending him to the United States for two years. Xie left for the Unites States in November of that year. This was another major turning point in his life, for it enabled him to begin to formulate his own philosophical and religious thought, a development which was triggered by his coming into contact with Western philosophy.

After arriving in America, Xie first enrolled in the winter term of Chicago University. He audited courses on “Social Theology” taught by the Dean of the Divinity School, Shailer Matthews. (Note: Matthews was a noted exponent of liberal, or modernist, theology, the conceptual foundation of the Social Gospel. He rejected orthodox Christianity in favor of an approach which subjected the Bible to “scientific” discoveries and criticism, resulting in a denial of miracles such as the resurrection of Christ and his second coming, as well as the need for regeneration and the hope of everlasting life).

He also attended lectures on “Comparative Religion” by Augustus Hayden; “Philosophy of Religion” by Henry Nelson Wieman (a proponent of religious naturalism), and “the History of Philosophy, taught by George Mead (an advocate of pragmatism and behaviorism). During this period he was also chosen to be the chairman of the Overseas Chinese Student Fellowship of Chicago.

In the fall of 1926,when he learned that the famed English philosopher Alfred North Whitehead was coming to teach Natural Philosophy at Harvard University, Xie transferred to that institution, where he took or audited a number of courses taught by distinguished professors, among whom were William Ernest Hocking, a proponent of New Hegelianism; Ralph B. Perry, who espoused New Realism; Whitehead, the one whom he admired most and who had the deepest impact on his own thought; and others, along with the Philosophy of Religion courses of George F. McClean and Edward Moore. Though he did not identify with any one of these particular schools, what he received from these outstanding teachers proved useful to him for the rest of his life, far surpassing what he had gained in Japan. Returning to China in 1927, Xie wrote On Character Education and Philosophy of Religion for the YMCA, works heavily influenced by Western philosophy.

Xie Fuya began his university teaching career at Lingnan University in 1928. Three years later, he assumed leadership of the Department of Philosophy. While teaching at Lingnan, he published a number of books, including: A Philosophy of Life, ABCs of Chinese Ethical Thought, Ethics, Essentials of Christianity, A Personal Gospel, etc.. He also edited the Lingnan Journal. In addition, he invited many noted scholars to Lingnan for academic exchange or to lecture. These academic activities opened the eyes of young students, and also elevated the prestige of the university’s liberal arts program in China. Chinese and foreign scholars he invited included a famous professor from Japan, professor Hocking from Harvard, Hu Shi, Zhang Junli, and others. His teaching career at Lingnan can be said to have been the second high point in his life.

During summer vacation in 1934, Xie took a group of Lingnan students to visit Japan. Upon returning, he saw afresh the conditions in both cities and rural areas, and was moved by his nation’s sufferings and hardship, especially the poverty and backwardness of farmers. At the same time, he sensed that China’s potential lay in its countryside, and wrote articles on topics such as “the Christian Mandate in Today’s China, “Excessive Worry over China’s Future,” and “The Forecast for China’s Future,” in which he earnestly summoned China’s youth to go to the countryside. Xie himself led the way by his own example. Resigning his professorship in 1936, he left his ivory tower to invest himself in the work of masses. Moving to an experimental district in Ding County, Hebei, to become Executive Secretary of the China Mass Education. In the course of his work, he went to Changsha, Sichuan, Chengdu, Chongqing, and other places, helping the local cadres in training workers. He published a small series of books for the people, helped Yan Yangchu to compile the “Thousand Character Course” to serve as a resource for literacy education, and edited several reference works. He sought to deliver the people from “foolishness, poverty, weakness, and selfishness.”In 1937 he wrote Christianity and Modern Thought.

Xie returned to his teaching at Lingnan in 1939. Because of the impact of the Japanese invasion of China, during the war he had to move to various places to continue to teaching. In 1940, he assumed the post of Principal of the School of Literature and director of the Research Institute of Zhong Shan (Sun Yat-sen) University. Responding to the invitation of Liao Shicheng, he became director of the Citizen Education Institute of Hunan Normal University. Then in 1943 he became the Dean and also in charge of the Department of Literature of Soochow University. He translated Josiah Royce’s Philosophy of Religion in 1944. He joined the faculty of the Xijiang River Institute of Guilin in 1945. After the conclusion of World War II, he arrived in Chengdu, where he taught in the Rural Reconstruction Institute and worked in the National Translation Office. He followed the Translation Office when it moved back to Nanjing in June of 1946. After that he taught at Nanking University. In 1947 he served as general editor of a series of books on philosophy, published as Moral Philosophy.

Xie Fuya took his understanding of Western philosophy as he shared the calamities suffered by his country and endured the life of a destitute refugee. As an intellectual in a period of danger and difficulty for the masses, he could only use his pen to cry out on behalf of the poor, exhausted people, and to castigate the atrocities of the invaders and arouse the awareness of the general populace. He published a large body of writings, educated a great number of young students, while at the same time he “practiced what he preached” by taking part in rural reconstruction movements.

This was a period when he also pondered more deeply his own philosophical system and applied his ideas in practical ways. He continued to do research on Chinese and Western thought and comparative studies of Chinese and Western religion and culture, came to understand ways in which they were “different,” and thus complementary, and could absorb the best in the other. He also saw ways in which they were fundamentally the “same,” and the possibilities of ways in which they could be integrated with each other and forged into something new. This period was also when he began to take his thinking about the philosophy of life and ethics as the beginning. He had a foothold in the perspective he had already gradually explored of some elements of value from Western philosophy that could be applied to the Chinese context—-to express his Christian faith in the Chinese way.

In September 1946, Xie assumed the presidency of the Hunan Teachers’ College; later, in order to avoid the turmoil of the times, he removed to Guangzhou, becoming the chairman of the Department of Education of Overseas Chinese (Huaqiao) University, while at the same time teaching Philosophy of Life at Lingnan University. He left there quickly to escape to Hong Kong in 1947.At first, he accepted the invitation of Hong Gaohuang, the president of Ling Ying College, to establish a Department of Chinese and to offer a course on Ethics in the Education Department. A year later, financial difficulties forced the school to close its doors. He joined the faculty of the Hong Kong College of Language and Commerce in 1952. The next year, he moved to the newly established Chung Chi College to teach Chinese and History of Chinese Philosophy.

He began teaching at the new Hong Kong Baptist College in 1956. While in Hong Kong, Xie published a number of works, including Contemporary Moral Philosophy, the Philosophy of Life, An Introduction to Chinese Political Thought, A Survey of the History of Chinese Literature (or, simply, the History of Chinese Literature), and Ethics. He also contributed articles to various periodicals, such as the Chung Chi Journal, Friends of the Youth, Life, Ching Feng, and Salt and Light.

Although so many open doors lay before him in Hong Kong, Xie believed that the realities of Hong Kong society were not suitable for him. In April, 1958, he responded to the invitation of a Nanking Theological Seminary Trustee in New York and left Hong Kong for the United States to assume the work of translating and editing the series, Representative Writings from Christian History.

Thus began a twenty-year career of translation, during which he translated such works as Literature of the Early Christian Church, Selected Writings of the Eastern Fathers, Medieval Christian Thinkers, Theology of St. Thomas Aquinas, Anglican Theologians, Theology of the English Reformation, Kant’s Ethical Philosophy, Modern Idealism, Kierkegaard’s Philosophy of Life, Schleiermacher, Religion and Piety, The Devout Life: Selected Writings of Friedrich von Hugel. He also wrote Christianity and Chinese Thought; translate the Year of Jesus, by Kenneth Scott Latourette; and translated the famous work, From Jesus Forward. In addition, he composed several shorter essays that were published in different journals.

In his old age, Xie expended all his energy on translating representative works of Western religious and philosophical learning into Chinese; this was the third highlight of his life. Immersed in a foreign culture, he came to deeper appreciation of Chinese and Western cultures and how they could be melded together. From a Christian standpoint, he forged and then perfected his New Chung-ism philosophical system. In doing so, he developed and expressed his balanced and impartial, mediating theological thought, proposing an indigenous theology marked by concepts like Putting Faith into Practice . The works he wrote during this period, such as Christianity and Chinese Thought, Elements of Christianity, Principles of Christian Theology, abundantly expound his religious and philosophical program.,

Xie published his autobiography, in 1970. At the age of eighty, with the help of his friends, his collected works, coming to more than three million words, were issued in six volumes:

- The Philosophy of Life, Moral Philosophy, Philosophy of Religion, An Introduction to Chinese Ethical Thought, A History of Chinese Political Thought.

- The Outline of the Bible Expositions, A History of Chinese Literature, Syllabus for the Study of Rhetoric, A Critique of Famous Persons in Chinese History, A Guide for Living, Collected Scholarly Articles.

- Philosophy of Religion, An Outline of Christianity, Christianity and Modern Thought.

- Essays on Chinese Religious Thought, Christianity and China, An Introduction to Famous Persons in the History of Christianity, Sermons, the Spiritual Life, and other essays.

- From the May 4###sup/sup### Movement up to the War against Japan, The Period of the War against Japan and Recovery, Essays on Various Events since 1949 (the Change of Regime on Mainland of China).

- Poetry and Essays. Xie Fuya wrote most of the works in this collection, and from these we can trace the trajectory of the development of his thought and gain an appreciation for the elegance of his literary achievement, his philosophy, and his theology.

Xie lost the sight of both eyes in his later years but, relying on his sense of touch, he continued to write incessantly. Works composed during this period of his life include Reflections upon [My] Life, Discussions on the Book of Changes, Later Writings of Xie Fuya, Later Writings of Xie Fuya on Christian Thought.

In 1980 he accepted invitations from the government to visit Taiwan, where he lectured at Tunghai University and a number of theological seminaries. He returned to China in 1983 for a visit, and gave lectures at Sun Yat-Sen University, and at a number of institutions of higher learning and research institutes in Beijing, Nanjing, receiving a warm welcome from the Chinese government.

After three months, he returned to the United States, where for a time he collaborated with others to publish the journal, Overseas China. Owing to his age and declining strength, however, he was unable to continue this work and had to cease. He returned to China and settled permanently in Guangzhou In September, 1986. He invited friends to celebrate his one-hundredth birthday at the White Cloud Hotel. He died three months later in Guangzhou.

Xie Fuya was a transitional figure in the world of Chinese theology. Not only did he possess a solid and profound training in Chinese studies but, even more, he had a rich understanding of the Christian tradition. His research into comparisons between Chinese and Western cultures, and even more his mastery of both Chinese and Western philosophy, expressed in his discourses on the philosophy of religion, were farsighted and preceded those of most Western scholars by decades. He made breakthroughs in turning religion into philosophy, providing a new approach for those who were both prejudiced and narrow-minded towards Christian philosophy or the philosophy of religion, and thus providing a cross-cultural, cross-religions approach.

Having gone through the huge and historic changes that occurred between the founding of the Chinese Republic and the Opening and Reform movements (of the 1980s and following) in mainland China, having lived a long time overseas, … facing all kinds of epochal vicissitudes in society; and despite his long separation from his homeland, through his theological reflections Xie made a powerful impact and lasting impact. His life of wandering made his personal faith, his national identity, and his cultural role sources of his Chinese Christian theological thought.

In his life – the death of his father at an early age in his childhood, the frequent illnesses in his youth, the destitute and homeless wanderings in his middle age, and his life in a foreign land as an old man – he was representative of all those Chinese intellectuals over the past one hundred years who also endured similar disasters. Yet is was precisely these sorts of events and conditions that lent a sort of willy-nilly, even inevitable element to the various choices which Xie Fuya made at critical junctures in his life, including the illness that forced him to return from Japan to China, his move to Hong Kong in 1949 and then to the United States in 1959, and becoming an American citizen later, then his later return to Guangzhou and settling there in his old age. Because of the constant changes in his life and surroundings, his thought and his understanding of faith are marked to a certain degree by an imprecision stemming from constant difficulties and vicissitudes of life.

Accordingly, in judging his faith and theological thought, Xie cannot be considered a “born again Christian” in the traditional sense of the term; he was more like what is called today a “culture Christian.” In his last years, he several times referred in various essays to his conversion to Christ and his mother’s prayers to Guanyin as related to each other. He also described the Chinese classics, including the Odes, Classic of History, Book of Rites, and the writings of Confucius, Mengzi, and Laozi as China’s Old Testament, and said they could be connected to the New Testament of the “era of grace” brought by Jesus Christ (Later Writings on Christian Thought by Xie Fuya, 210).

When he returned to China in the 1980s, he even went so far as to connect the people engaged in the united front campaign of openness and reform in the economy to Jesus’s words, ‘You must be born again,” and their actions as expressions of repentance and turning from former errors. In addition, his concepts of the “Chinese Christian” and “indigenous theology” were heterodox. That he became a very controversial figure in Christian circles should not, therefore, seem strange. Perhaps he was correct when he observed, towards in his later years, “looking back over my life, I regret to say that I cannot be called a real, rather than merely nominal, Christian, but at the most I can only be called a “thoughtful scholar.”

Part Two: Thought

Four principal sources of Xie Fuya’s religious, ethical, and philosophical thought stand out from the biography above: His mother’s Buddhist piety; his early immersion in liberal Christianity and secular Western philosophy; his life as a wanderer and partaker in the chaotic, traumatic conditions of the Chinese people; and his deep study of Chinese philosophy and ethics. These he wove into a system that blended into what he hoped would be a comprehensive integration of Western and Chinese concepts suitable for modern Chinese people.

Though Xie thought of himself as a Christian, moved in Christian circles, and wrote books on Christian themes and with a Christian (as well as non-Christian) audience in mind, as the author of the biography above says, he was not an adherent of traditional Christianity, but a self-conscious forger of an “indigenous” Chinese Christian theology that melded elements of Christianity with those of traditional Chinese culture.

By the time Xie became involved in the YMCA, that originally evangelical organization had become a leading engine of the Social Gospel movement, not only in the United States, but also in China, where thousands of idealistic young Americans went to bring “progress.” Having long ceased to proclaim the evangelistic gospel of the nineteenth century, the “Y” promoted science and democracy, education and reform, women’s liberation and rural renewal.

Likewise, Xie’s studies in the United States brought him under the influence of leading liberal, or - as they were called then, modernist – thinkers within “mainstream” Protestantism. Whitehead’s process philosophy described a God constantly changing as he interacts in love with the world. Process Theology, which has spawned Openness Theology, derives directly from Whitehead, and departs fundamentally from the God of the Bible. In the mind of a man like Xie, however, such a philosophy of mutually influencing processes could support an integrative “indigenous” theology that allowed traditional Chinese and Christian ideas to blend and cohere into something new, both Chinese and Western, with Christianity providing the vocabulary and evocative images, though far removed from their original meaning.

William Ernest Hocking, one of Xie’s teachers at Harvard, supervised the famous (or notorious) report, Re-Thinking Missions: A Layman’s Inquiry After One Hundred Years (1932) and known as the “Hocking Report,” called for abandonment of traditional evangelistic and church-planting efforts, advocated more focus on educational and social welfare work, and affirmed the value of other religions. These ideas would later find similar expression in Xie’s work.

Xie Fuya was one of several Chinese Christian intellectuals who tried to combine traditional Chinese religion and philosophy with Christianity to form an “indigenous” theology that emphasized perceived similarities between the different faiths and downplayed the differences. Each had his own particular parts to play in this movement.

The Chinese theologian Lit-sen Chang (Zhang Lisheng), once an enemy of Christianity, was converted to Christ as a mature man. He then wrote prolifically, seeking to convince his fellow Chinese intellectuals, and especially proponents of Indigenous Theology, that only biblical Christianity could really save China. In his Critique of Indigenous Theology, he discusses Xie Fuya’s thought at some length, in the process quoting extensively from Xie’s writings. The following brief discussion relies on these quotations.

In Xie’s eyes, the doctrine of the Trinity is basically the same as several traditional Chinese concepts, which take their starting point from man, not God. For example, “the Holy Spirit is nothing other than the personification of love and goodness” found in the classic, Doctrine of the Mean. God himself is the “Supreme Oughtness, the heavenly principle of which the rationalistic school of Confucianism spoke.” “The unfathomable interaction of yin and yang is what we call ‘god.’”

Averse to unchanging truths and doctrines, he states that “Chinese Christianity can have different conceptions of God in different ages and in each individual person.” The reason is that “since philosophy is the foundation for theology, and since there are differences among Chinese, German, Greek, Roman, etc. philosophies, theology will also differ according to people and era.” “The conception of God must be adjusted according to developments in society and in the times.” With this in mind, Xie called for “a ‘Chinese Bible’ the ‘creation of a New Chinese Christianity’ and an ‘independent electorate’to arise and oppose God and establish the kingdom of heaven to break free of ‘God’s monopoly’ [on power].”

Like Whitehead before him and contemporary Openness Theologians, Xie rejects what he terms the “despotic tyrant” nature of the biblical description of the God as King. Also like Whitehead, Xie believes that to say that God is “omniscient, omnipotent, all-loving, omnipresent, one, absolute, infinite, eternal, etc.” is to make him “unnatural and unreasonable.”

Xie explains Jesus’s claim,” I am the way, the truth, and the life,” to mean: “the way is the realization of democracy, truth is the goal of science, and human life is the nexus where the highest truth and the ultimate way may be intimately combined.”

As for Jesus’s statement that he came not to abolish the Law and the Prophets, but to fulfill them (Matthew 5:17), Xie writes, “To fulfill it is to instill a fresh rationality in the old law; then the parts that are moribund will naturally dissipate and disappear. The greatest expression of this fulfillment of the Law will be service to society and the extension of God’s kingdom.”

On Christianity’s relationship to traditional Chinese religions, Xie says, “Christianity is very close to China’s Northern Zen Buddhism.” Like the Jews, “the Chinese also had their religious concept of reverence and fear toward Heaven, as well as their historical prophets, … We really feel that they also respond to and reflect part of God’s revelation, and see them as a type of the New Covenant (New Testament). Whether it be Confucian or Daoist, or Chinese Buddhism, the excellent parts of this literary corpus are sufficient to merge with the religion of Jesus Christ without any cause for shame or even shyness.” He asserts that “Christianity did not come to China to overthrow ancestor worship or the worship of Heaven and Earth.”

Of all the religions, Buddhism is the most superior, because it “understands the self and elevates the self.” Traditional Christianity, to Xie, is “an enemy of progress, a running dog of imperialists, a misleading, intoxicating poison for the youth.” With their broad love for others, Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism far surpass Christianity in value.

Reflecting his background in the Social Gospel Movement and his involvement in rural reconstruction, he writes, “The mission of Christianity in China today is to organize a great revolutionary movement. A people’s revolution, social revolution, and spiritual revolution… The revolution of Jesus naturally follows in accordance with the revelation of God on the one hand, and on the other hand he secretly listens to the cry of the masses… The gospel of peace is nothing other than the gospel of struggle; preaching the gospel of peace has already failed. God has come to bring a sword to the earth! (Matt. 10:34) …

Xie’s roots in rationalistic Western philosophy bear fruit in sentences like this: “The rise and fall of religion is directly proportionate to the degree of its rationality,” and his belief that the idea of “salvation by faith” is improper. Paul’s conversion to Christ, accordingly, is described as “a form of mental illness.” Thus, he can say that “the wiser men of today, who put into practice the faith of God” are “those who draw their strength from the ontology of Aristotle, Spinoza, and Kant.”

For him, true religion comes from below, not from heavenly revelation: “The religious spirit is learned from society, and is formed gradually from the interaction of the individual and society upon each other.” “In order for it to be of any benefit to us, our faith must submit to the limitations of reason.” That is why, in his view, “Protestant theologians whom we now call ‘Modernists’ (who oppose the Fundamentalists) are working hard to build a new theology on the basis of reason… Their future is very bright.”

Rather than salvation by grace through faith in the redemptive work of Christ on the Cross for sinners, Xie sees being “born again” or “saved” as “nothing other than an emphasis upon the effort of self-cultivation,” as in Confucianism and Buddhism. Since there is no life after death, being “born again” can be Buddhism’s “combining of Atman with Brahman, the Nirvana of Buddhism,” or Laozi’s “to devote oneself to the nation and thus to become with the nation.’”

Evaluation

From the brief biography in Part 1, we can see that Xie Fuya combined great learning, devotion to the welfare of the common man, and years of hard work to produce a massive body of writings on a wide variety of subjects, including the similarities between Chinese and Western cultures and religions.

From Part 2, we can understand why the author of the biography in Part 1 describes Xie as more like the “culture Christians” of recent decades than what Chinese Protestants, most of whom are conservative evangelicals, would term a “born again Christian.”

Theologically, he stood firmly in the liberal camp, consciously rejecting traditional, orthodox, biblical Christianity. Proponents of a mediating “indigenous Chinese Christianity” may find him attractive. Those who hold to the authority of the Bible and the ecumenical creeds will look elsewhere for a theology that both speaks to Chinese culture and remains faithful to Scripture.

Sources

- 谢扶雅著,《巨流点滴》,香港基督教文艺出版社,1970年。

- 何慶昌著,《謝扶雅的思想歷程》,臺灣基督教文藝出版社,2013年。

- 網路資料:唐曉峰,《謝扶雅先生小傳》。

- 百度人物詞條。

About the Author

Director, Global China Center; English Editor, Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.